Mitigation & Conservation Banking for Northern Colorado Landowners — Quick Q&A

This guide provides a fast, plain-English overview of mitigation and conservation banking for landowners and partner organizations in northern Colorado. This guide is not legal advice. Final requirements of mitigation and conservation banks are set by governmental regulators and through landowner agreements.

Quick Q&A

What is this?

Mitigation and conservation banking are well-established regulation-driven markets. When development projects impact streams, wetlands, or wildlife habitat, the law requires those impacts to be offset. One way they do this is by buying “credits” from approved banks. A bank is created when land is restored or protected so it provides measurable ecological value. Those improvements are converted into credits, which can then be sold to buyers who need them. For landowners, this means your property could generate credits — and income — if it has habitat, wetlands, or streams suitable for restoration or protection. You keep ownership of the land, but agree to certain long-term restrictions in exchange for sharing in credit revenue.

What are the benefits to landowners?

• Healthier land. Restoration can stabilize eroded streambanks, improve grazing conditions, increase water quality, and enhance fish and wildlife habitat. These changes can also reduce long-term land management headaches.

• Earn new income. By leasing land to a bank developer, you share in credit revenue without paying for studies, permits, or restoration work yourself. Participation does require some changes in how parts of the land are used, such as limiting livestock access to sensitive stream areas or adjusting grazing schedules.

• Long-term value. Permanently protected, high-quality land often appeals to conservation buyers and can hold its value over time.

• Leave a legacy. Banking helps conserve northern Colorado’s rivers, wetlands, and wildlife — while keeping your land working for future generations.

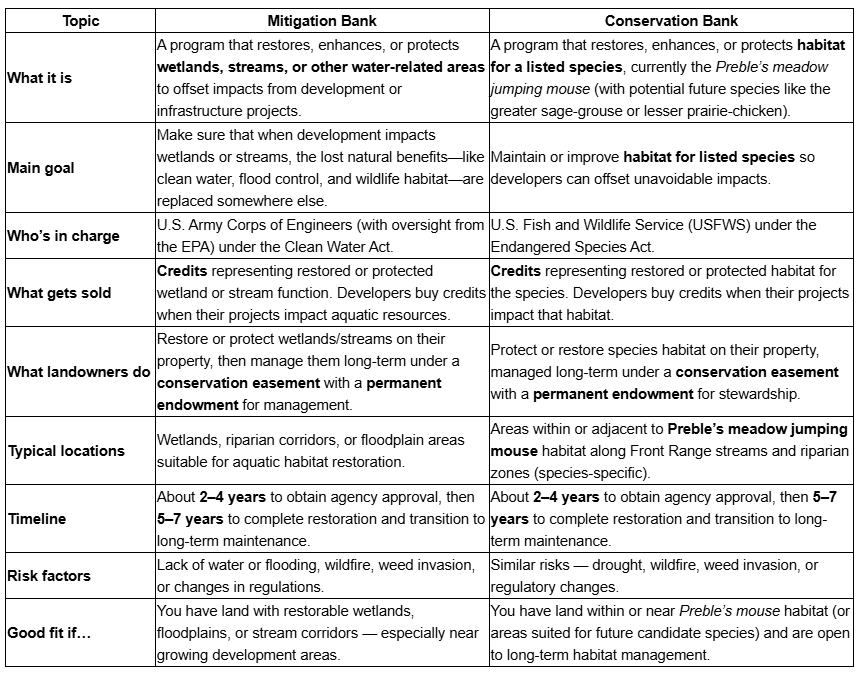

What’s the difference between conservation and mitigation banking?

Both types of banks create credits by restoring or protecting land, but they focus on different resources:

• Conservation banking = species habitat credits.

In Larimer County, the only current species covered by conservation banks is the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse. These banks are overseen by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

• Mitigation banking = wetland and stream credits.

This means repairing eroded streambanks, reconnecting floodplains, or improving wetlands so water runs cleaner and healthier. These banks are overseen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, with input from the EPA. Sometimes a single project can support both — for example, restoring riparian wetlands may also create mouse habitat. In those cases, one site may qualify for both types of credits.

How do I know if my land might qualify?

You don’t need pristine land to qualify. In fact, land that needs restoration is often the best fit. Common signs your property may work include:

• Streams: A creek that runs most years but has eroded banks, down-cut channels, or a disconnected floodplain. Restoration often means reshaping banks, planting willows or cottonwoods, and reconnecting the floodplain.

• Wetlands: Natural wetlands that have been drained, invaded by weeds, or don’t hold enough water. Restoration could involve removing invasives, adjusting water flows, or re-establishing native wetland plants.

• Riparian corridors: Habitat along streams or rivers that could support the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse. Work here may include fencing certain areas, planting native vegetation, and managing grazing timing to protect cover and food sources.

The first step is usually a desktop screen (reviewing maps and photos), followed by a short site visit from a bank developer or biologist to confirm feasibility.

What will be required of a landowner?

If your land is used for a bank, you keep ownership but commit to certain long-term protections and management. Typical requirements include:

• Perpetual site protection: The restored area is permanently protected, usually through a conservation easement.

• Compatible land use: Some activities may be limited, such as unrestricted grazing in riparian areas, vehicle access, or water diversions. Managed agriculture often continues, but with timing and methods adjusted to meet habitat goals.

• Long-term management: Habitat must be maintained in perpetuity. This can include weed control, replacing fences, or managing grazing. The bank developer provides an endowment at the time of approval to cover these costs, whether the work is done by you or a contractor.

What’s the process?

A. Regular Bank Process

• Site assessment and screening: The bank developer evaluates your land (streams, wetlands, habitat, credit potential, and market demand).

• Lease negotiation: You and the developer agree on lease terms, payments, and land-use restrictions.

• Studies, design, and approvals: The developer leads technical studies, designs the restoration plan, and works with agencies to secure approvals. This stage usually takes 2 to 5 years.

• Easement, restoration, and credit sales: You grant a conservation easement. The developer funds and carries out restoration, begins monitoring, and sells credits in phases. You receive your share of credit revenue.

• Long-term management: The developer sets aside an endowment to pay for ongoing stewardship. The work can be done either by you or by a contractor. In both instances, costs are covered.

B. Umbrella Bank Approach

Umbrella Banks are pre-approved frameworks that allow multiple sites to be added under a common agreement. The Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse Umbrella Bank is the state’s first, though umbrella banks are common in the eastern U.S. Benefits of the Umbrella Bank versus a regular bank

• Shorter approval timeline – new properties can be approved in months, not years.

• Reduced risk – you know from the start how many credits your property will generate, what restrictions will apply, and what your compensation will look like because it is already approved and documented.

• Clarity from day one – no need to wait years to know if your site is viable.

Quick glossary

Credit: The unit that is sold in the market. It represents restored or protected species habitat, wetlands, or streams. Buyers like real estate developers and utilities buy these credits to offset their impacts.

Service area: The geographic region where your credits can legally be used by buyers. Defined by regulators, not by the landowner or developer.

Bank developer: The entity that designs, funds, permits, restores, and sells the credits. They carry most of the costs and technical work.

Conservation easement: The legal agreement that permanently protects the restored area of your land and sets the rules for its use. You still own the land.

Instrument: The formal agreement between the bank developer and agencies. It defines how credits are created, released, monitored, and managed over the long term.

Umbrella bank: A pre-approved banking framework. Developers can add new sites under it quickly and with more certainty about credits, restrictions, and payments.

What to do next?

If you think your land might qualify, there are two easy first steps:

Free screen: Share a parcel map and a few photos of your stream, wetlands, or riparian area. The developer can give you a quick yes/no on whether it’s worth pursuing.

Field walk: Schedule a 60–90 minute visit with a bank developer or biologist. They’ll ground-truth feasibility, explain likely restrictions, and discuss lease options. These steps are low-commitment ways to see if banking is a fit before making any decisions.

If you are interested contact: Ben Guillon - Ben@conservationinvestment.com - (720) 443-3879